A History of Reinvention

Houston continues to change with the times as it learns to celebrate its rich and successful past.

By Cynthia Lescaleet

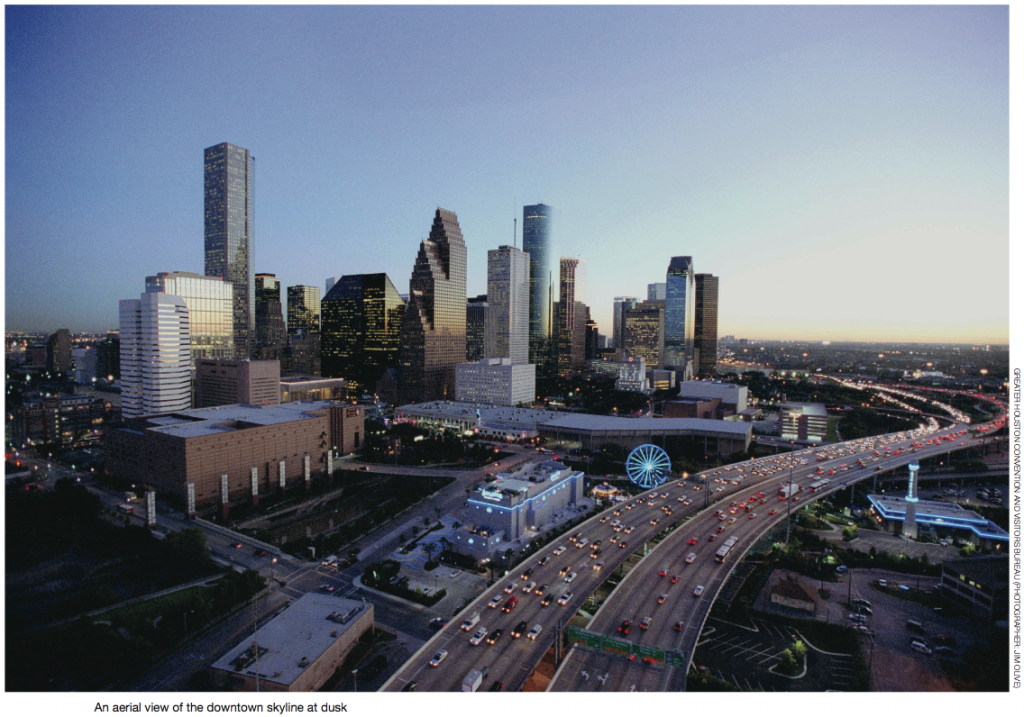

Even a city focused on its future has a history. That paradox helps explain Houston past and present. It is a city built on ideas realized and enterprise rewarded, an enduring culture of vision, ingenuity and drive that has wrought lasting, far- reaching results. Even today, a diverse population continues to be attracted to the city’s opportunities and possibilities.

“It’s not about who you are and where you came from, it’s about your idea,” explains Greg Ortale, president and CEO of the Greater Houston Convention and Visitors Bureau. Houston Ship Channel, the Texas Medical Center and NASA’s Johnson Space Center are all symbols of innovations from Houston’s past with ongoing impact, he says.

Despite being a young city not known to dwell on its past, Houston fascinates city historians. Betty Trapp Chapman, a historian, city-honored preservationist and author, suggests there is a theme woven through Houston’s story that is still unfolding: “We’re always doing the unexpected,” she observes. “There’s always a group of people who say, ‘Let’s get it going.’ ”

Consider Houston’s founding in August 1836, just months after the Republic of Texas emerged an independent nation from territory controlled by Mexico. Brothers Augustus Chapman Allen and John Kirby Allen, land speculators from New York, were scoping out potential town sites as they navigated the inland waterway from Galveston Bay. When they reached the wide confluence of Buffalo and White Oak Bayous, they envisioned a viable site for commerce, industry and the people who would make it thrive. From the initial 6,624 acres the brothers purchased has grown a city about 600 square miles in size. Houston is now the fourth-largest city in the U.S., home to 2.1 million people, according to 2010 census figures.

Consider Houston’s founding in August 1836, just months after the Republic of Texas emerged an independent nation from territory controlled by Mexico. Brothers Augustus Chapman Allen and John Kirby Allen, land speculators from New York, were scoping out potential town sites as they navigated the inland waterway from Galveston Bay. When they reached the wide confluence of Buffalo and White Oak Bayous, they envisioned a viable site for commerce, industry and the people who would make it thrive. From the initial 6,624 acres the brothers purchased has grown a city about 600 square miles in size. Houston is now the fourth-largest city in the U.S., home to 2.1 million people, according to 2010 census figures.

Today, the spot where the founders landed, called Allen’s Landing, is but a grassy slope rising from the waterline at the base of Main Street. The site can only hint at the vital role it played in the city’s growth and evolution, says historian Mike Vance, the executive director of Houston Arts & Media and primary researcher on the nonprofit’s “Birth of Texas” documentary series.

Houston, the city, was named for Sam Houston, the general whose small force of “Texians” (meaning Anglo Texans of the time) defeated Gen. Antonio López de Santa Anna’s Mexican Army at the Battle of San Jacinto, thus achieving Texas’ independence.

In naming their town, the brothers Allen had correctly anticipated that Sam Houston would become the new republic’s first elected president. Their efforts to land Texas’ seat of government also included building a Texas capitol in yet- to-be-built Houston and giving town lots to Sam Houston and other key legislators, Vance says. The outcome was successful—albeit brief. Houston was Texas’ temporary capital city from 1837 – 1839. Subsequent Texas leadership moved the new republic’s capital to a more central and eventually permanent location in Waterloo, better known as Austin. Texas accepted U.S. statehood in 1845, the state seceded during the Civil War and was reinstated in 1870.

A tidewater outpost, early Houston was rustic and rough, complete with dueling grounds for the bachelor-heavy population. A nefarious element drew the colorful epithet “Rowdy Loafers” in journals and news accounts of the time, Vance says.

Honed by passing years, Houston cultivated unique attributes to temper these rugged frontier roots, Chapman says. “We’re not really Western,” she explains. “We’re more Southern. But not typical of either (region).”

Honed by passing years, Houston cultivated unique attributes to temper these rugged frontier roots, Chapman says. “We’re not really Western,” she explains. “We’re more Southern. But not typical of either (region).”

This hybrid cultural heritage sometimes surprises visitors to Texas’ largest city, says Orlando Rivera, owner of See and Do Tours. Those visitors often ask him about iconic cowboys and ranches, despite Houston being a modern, international city in population and outlook. As his tours wind through downtown Houston’s historic district, guests encounter a revitalized Market Square and re- purposed Rice Hotel on the site of the first capitol. They also pass a collection of historic buildings on display in Sam Houston Park, the site of Houston’s first city park in 1899. Nearby rise the iconic skyscrapers from the oil boom era of the 1970s. The bottom line—no ranches but plenty of oil business.

Growth is Big Business

“Business has always driven Houston,” Chapman comments. She says this helps explain why there is little physical history as far as buildings are concerned. “When business drives a city, it focuses on how business development will grow the city’s economy. Houston had many ‘boom’ periods of growth when everything seemed too small and obsolete. So, they tore down what they had and built something larger and more ‘modern.’ That is why we have so little by way of visible remnants of our past.”

“Business has always driven Houston,” Chapman comments. She says this helps explain why there is little physical history as far as buildings are concerned. “When business drives a city, it focuses on how business development will grow the city’s economy. Houston had many ‘boom’ periods of growth when everything seemed too small and obsolete. So, they tore down what they had and built something larger and more ‘modern.’ That is why we have so little by way of visible remnants of our past.”

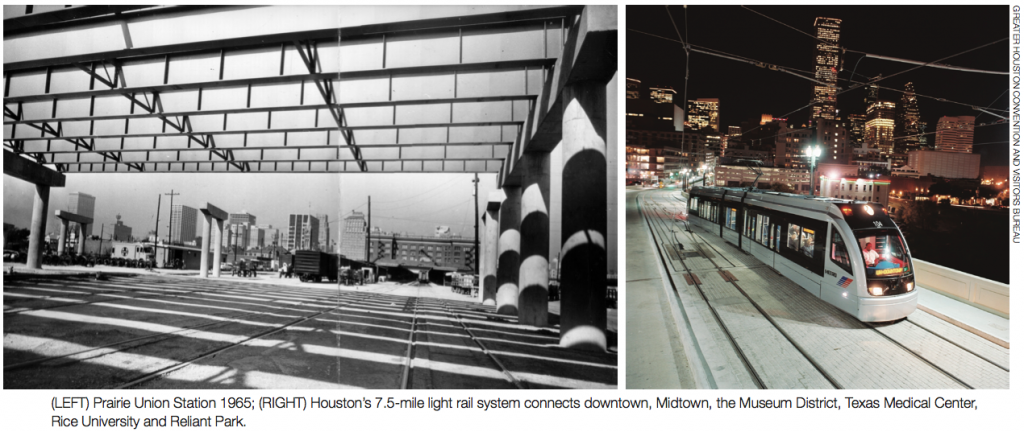

Houston’s economic evolution shifted focus from agricultural trade to industry. In the 19th century, plentiful lumber in the region and plantation crops of cotton and sugar—and later rice—gave way to 20th century oil and gas production, petrochemicals, banking, medicine, space and energy, with high-tech a newer arrival. Transportation has been another pivotal industry here all along, Vance says. “The things transported have changed, but the need to transport has not.”

And then there’s real estate itself, he adds, which has formed the backbone of many Houston fortunes. “The most well-off Houstonians of the late 19th and into the 20th century might have started their fortunes with lumber and cotton, but most grew through real estate,” he says. They viewed the city’s continued growth as an engine for bringing them a profit, he says.

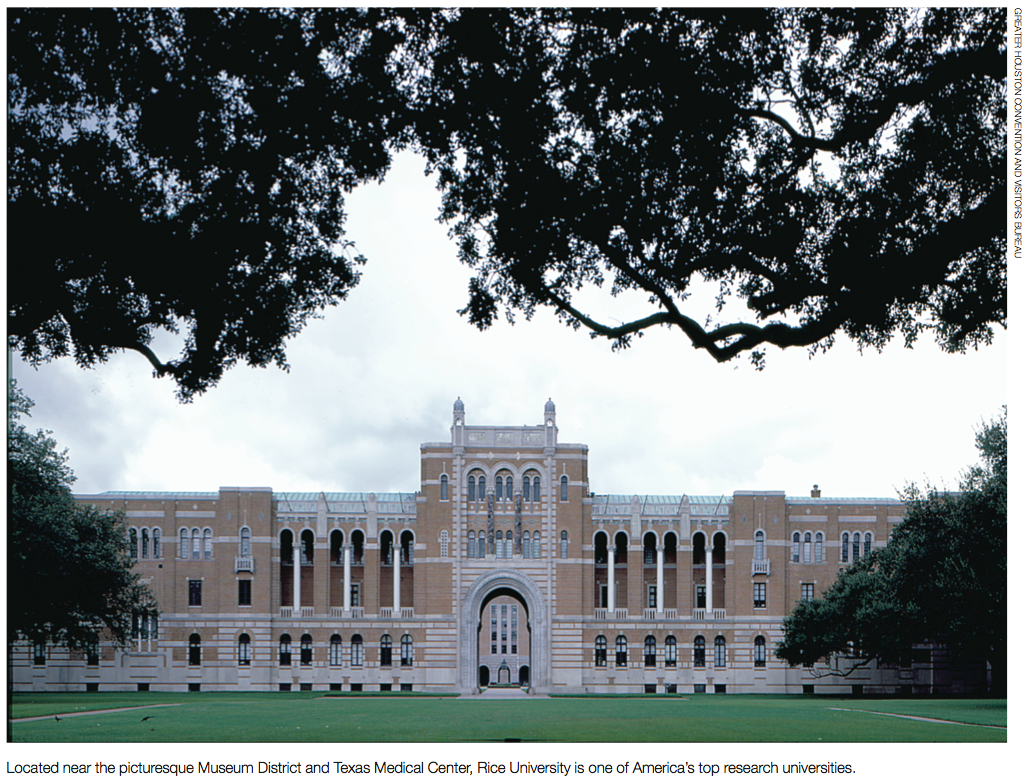

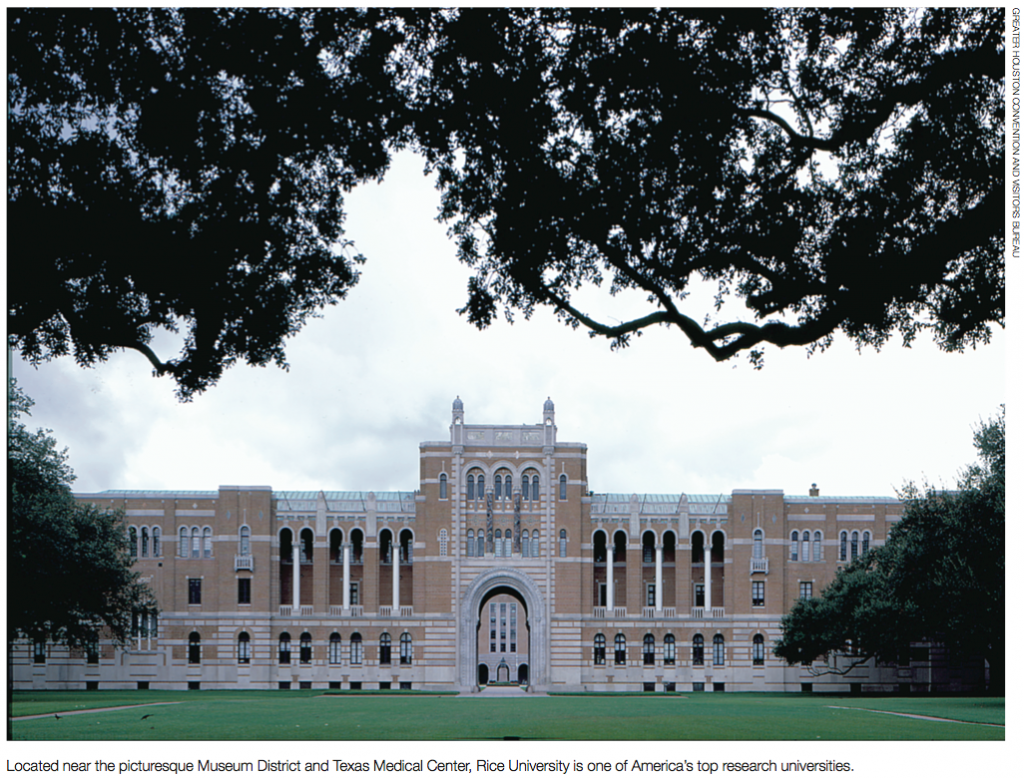

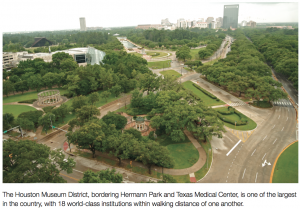

Chapman credits the strong business community with a number of city improvements: helping Houston get its deepwater port; playing a part in preventing its banking institutions from failing during the Great Depression; and supporting the formation of Texas Medical Center. Chartered south of downtown in 1945, Texas Medical Center’s campus now incorporates 49 medical, research, health care, scientific and educational institutions. Pioneering procedures in heart care and cancer treatment are among the life-changing advancements emanating from its members.

Chapman credits the strong business community with a number of city improvements: helping Houston get its deepwater port; playing a part in preventing its banking institutions from failing during the Great Depression; and supporting the formation of Texas Medical Center. Chartered south of downtown in 1945, Texas Medical Center’s campus now incorporates 49 medical, research, health care, scientific and educational institutions. Pioneering procedures in heart care and cancer treatment are among the life-changing advancements emanating from its members. Business interests also supported other entities that would bring dollars into the city, such as the arts, Chapman says. “The business community finally realized that cultural offerings were positive additions to a progressive city. Yet, as was often true, the city deferred to individuals and depended on them for the arts, education and social service—all those things that bring quality of life to a city. Out of the business community evolved significant philanthropists and philanthropic foundations, which today still basically fund these quality-of- life entities.”

Business interests also supported other entities that would bring dollars into the city, such as the arts, Chapman says. “The business community finally realized that cultural offerings were positive additions to a progressive city. Yet, as was often true, the city deferred to individuals and depended on them for the arts, education and social service—all those things that bring quality of life to a city. Out of the business community evolved significant philanthropists and philanthropic foundations, which today still basically fund these quality-of- life entities.”

Down on the Bayou

Historically speaking, having a bayou system differentiated Houston from other early settlements in southeast Texas, says Louis Aulbach, waterway expert, historian and author of newly released “Buffalo Bayou: An Echo of Houston’s Wilderness Beginnings.” It meant year-round access to water and a navigable link to Galveston Bay—and thus to the Port of Galveston for trade and passengers alike.

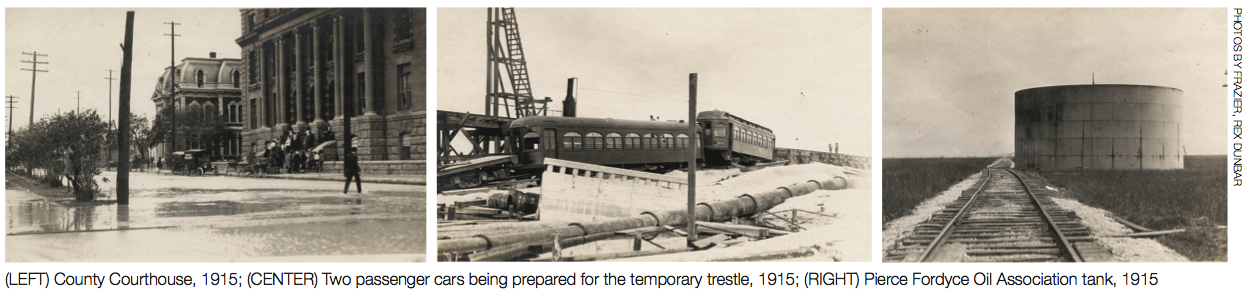

As a natural resource, however, Houston’s bayous also fought back against the city’s development. Floods, waterborne illness and mosquitoes bearing yellow fever, for example, toyed with the growing population, as have hurricanes and massive storms. More modern examples include Hurricane Carla in 1961, Tropical Storm Allison in 2001 and Hurricane Ike in 2008. Houston is a city that has learned how and when to hunker down and when to lend a hand, such as when Hurricanes Katrina and Rita in 2005 hammered neighboring Louisiana, sending 200,000 devastated refugees here.

As a natural resource, however, Houston’s bayous also fought back against the city’s development. Floods, waterborne illness and mosquitoes bearing yellow fever, for example, toyed with the growing population, as have hurricanes and massive storms. More modern examples include Hurricane Carla in 1961, Tropical Storm Allison in 2001 and Hurricane Ike in 2008. Houston is a city that has learned how and when to hunker down and when to lend a hand, such as when Hurricanes Katrina and Rita in 2005 hammered neighboring Louisiana, sending 200,000 devastated refugees here.

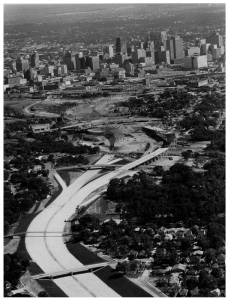

As Houston expanded in the mid-19th century, a rail system emerged to serve its nascent industries, predominately located on the north side of the bayou. In the 1850s, Houston had five rail lines. In the 1880s, its role as the Southwest’s transportation center had solidified with a railroad-to-shipping network connecting markets in the region, across Texas and beyond, Aulbach explains. By the early 20th century, bird’s eye view maps of Houston touted the city as “Where 17 Railroads Meet the Sea.”

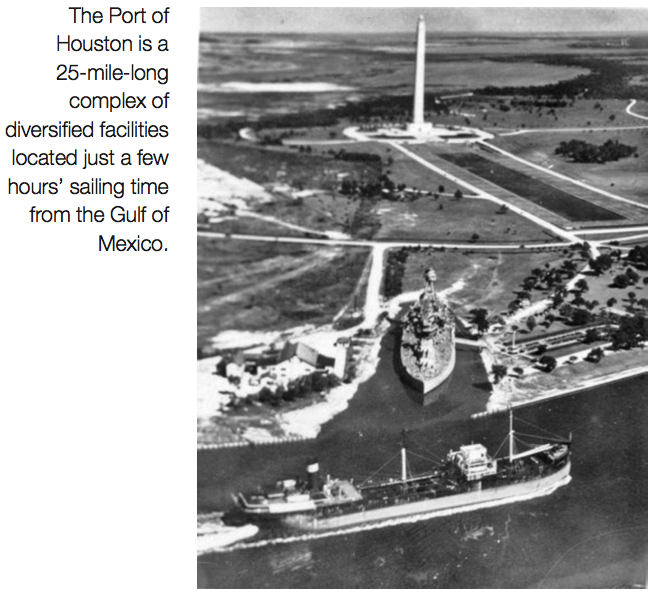

Concurrent to railroad expansion, Houston sought to improve its natural-but-shallow bayou channel to have a port of its own. The intent began in 1842. Congress granted Houston its port of entry status in 1870, and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers surveyed the channel. Despite some early federal seed money, the languishing project took until 1914, when it was spurred by a then new idea for private-public funding pitched by prominent Houston business leaders. Deepened to 25 feet, Houston Ship Channel completed its 50-mile deepwater slice inland from the Gulf of Mexico to a new turning basin for ocean-going vessels. Industries and transportation modes soon amassed along its boundaries, fueled by the 1901 discovery of oil at Spindletop in Beaumont, Texas.

Early Houston wasn’t the only locale with suitable transportation attributes, Vance says. However, the city was relentless in pursuit of becoming the unquestioned hub: “We had better, more aggressive business people,” he says.

About 150 industrial operations line today’s Houston Ship Channel, which is part of the Port of Houston complex. The port ranks second in tonnage (200 million tons of cargo each year) in the U.S. and is expecting to benefit from the Panama Canal expansion, according to the Port of Houston Authority.

Meanwhile, Houston’s bayou system appears to be gaining some appreciation after a long tradition of hiding it, straightening it, lining it with concrete and ignoring some of its park-like possibilities, Aulbach says.

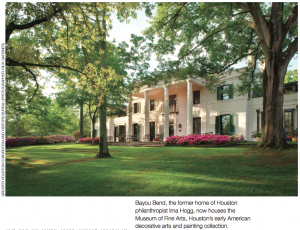

Bayou Bend, the former home of Houston philanthropist Ima Hogg, now houses the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston’s early American decorative arts and painting collection.

From Outpost to Outer Space

Houston’s lack of zoning is unusual for a city its size, Aulbach says. The lack of zoning sets up a dynamic in which everything can be new, he explains. “Every generation has a new frontier.”

Some frontiers have been literal: a tidewater outpost, an incubator for the oil and gas industry and a center for modern space exploration. Other frontiers have been more targeted as “firsts,” such as having the nation’s first public television station, first successful human heart transplant, first air ambulance program—and the proudly claimed first word uttered on the moon, according to the Greater Houston Convention and Visitors Bureau. Nanotechnology also took root in Houston, and some claim even zydeco music sprang from the city’s ever-shifting population, which is steeped in multi-cultural traditions.

Houston’s melting pot vibe is palpable to visitors from around the world, Rivera says, who meets a global village as part of his regular workday.

At Rice University’s Kinder Institute for Urban Research, co-director and sociology professor Stephen Klineberg has tracked the modern transformation of Houston as it occurs for the past 30 years, based on his annual Houston Area Survey of population and attitudes. He considers himself not a historian (“past-ologist”), but a “present-ologist.” Still, he says, Houston is making history now by having reached the demographic milestone of being the most ethnically diverse city in the country. That means Houston’s population distribution of Latin American (41 percent), Anglo (33 percent), African-American (18 percent) and Asian-American (8 percent) is in greater statistical balance than in any other major American city, according to the 2010 census.

“The city is in the process of reinventing itself,” Klineberg says. “We’re in a new historical period. It’s similar to the past, but different.” While early Houston grew by attracting migrants from elsewhere in the country, today, it’s immigrants and the children of immigrants who are transforming the city.

Houston’s population distribution is a model of what the U.S. will become by 2045, the census predicts. “How we navigate this transition has importance beyond Houston.”

175 Years Young

Vance notes that existing documentation of Houston’s past is not prevalent, not very diverse and not a full accounting, though this is changing as general interest increases. He attributes this shift in part to the city observing its 175th anniversary in 2011, with several neighborhoods and communities nearing their centennial milestones.

Houston is still a pretty young town, Chapman says. “I think we have slowly begun to appreciate what has come before. Perhaps it is a matter of maturing now that the city is 175 years old. It was always such a young city that it didn’t feel it had a significant past. However, we have learned that the arts, et cetera, will bring tourists and that is often considered important by those relocating to Houston. I think we are learning to tout these things.

“I believe we are making strides in historic preservation,” Chapman adds. “Again, perhaps, it is because we are maturing and have a better understanding of what the past can mean to a community. Knowing how a city came to be can help tremendously in deciding where it heads in the future because a city can learn from its past successes and failures. And, of course, I feel that we learn from not only being told these things, but also by seeing and experiencing the tangible aspects of our history—our buildings, neighborhoods, bayous, parks, et cetera. You can certainly gain an appreciation for those persons who came before and laid the foundation for what we have today.”