See captivating pieces of artwork by just strolling along the streets or tilting the head upward in some the most iconic buildings in North America.

By Dana Nichols

Murals can be historical, contemporary, political or picturesque. Whether laden with heavy symbolism or heartening folklore, murals, by their inherent nature, are meant to spark conversation and public appreciation.

“Public murals sharpen our focus,” explains Southern California-based artist Wyland, who is known professionally by just his surname. “They tell people that something is important and requires their attention. In many ways, public art has shaped our culture since the beginning of civilization. It is one of the most impactful visual resources in the world.”

Here, Bespoke Magazine highlights five North American murals that each communicates the pulse of its great city. From the old to the new, all are worthy of being in museums; thankfully, they’ve weathered the real, wide-open world, surviving through natural phenomena and stages of urbanization to delight generations of travelers to come.

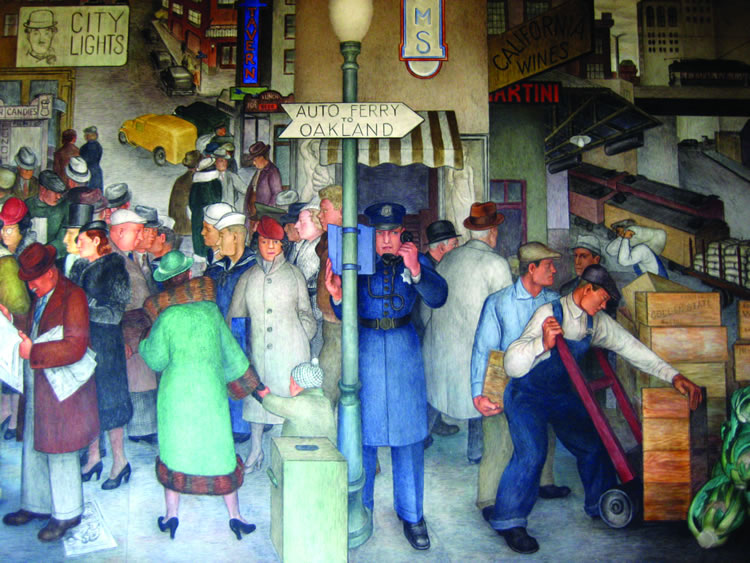

Public Works of Art Project

By Ray Boynton, John Langley Howard, Clifford Wight, Bernard Zakheim, Jane Berlandina and 20 others (1934), Coit Tower, San Francisco

The 27 murals that line the interior walls of Coit Tower represent a significant time in San Francisco’s history, and their rehabilitation this year by the city arts commission is a reminder that preserving such storytelling is paramount. Since its inception, the 210-foot tower’s art has been a topic of discussion and debate. In fact, it was padlocked to the public for three months before it opened in October 1934 due to controversy over what was then considered radical content in the frescoes.

“Each mural contributes to the whole experience and helps bring the visitor back to a very turbulent time in San Francisco’s history,” explains San Francisco City Guides tour guide Rory O’Connor. “They were painted in the midst of the worst years of the Great Depression and an increasingly bitter, and eventually deadly, labor dispute was taking place all along the waterfront, in plain view of the artists as they worked.”

The 25 artists were hired as part of a project funded by the Civil Works Administration and led by Ray Boynton, a painting instructor at the California School of Fine Arts, the precursor to the San Francisco Art Institute. He was experienced in fresco painting, while others, such as sculptor Ralph Stackpole, were new to the medium. The artists were a tightknit group, painting one another’s likenesses in their work, which they would, ironically, need to defend later before the public opening. In Bernard Zakheim’s “Library” in the Coit Tower, the artist depicted fellow artist John Langley Howard taking a copy of Karl Marx’s “Das Kapital” off the shelf.

“Zakheim couldn’t have been more direct about how he thought the economic crisis of the time ought to get solved, and it created immense controversy within the establishment in San Francisco at the time, and led to calls to censor the murals altogether,” O’Connor says.

The artists banded together when officials ordered Clifford Wight’s capitalism, New Deal and communism symbols to be removed. The artists, who didn’t want to comply, formed a picket line around the building to protect their masterpieces. In the end, the images were gone when the tower opened, yet the history and symbolism behind the artwork remains.

‘Epic of the Mexican People in their Struggle for Freedom and Independence’

By Diego Rivera (1935), Palacio Nacional de Mexico, Mexico City

It is often said that one photograph is worth a thousand words. In the case of Diego Rivera’s most famous mural, one man’s painting is worth 2,000 years of history. Mexico’s annals are detailed from the Aztec empire to the 1930s in this massive triptych work, which took the artist more than 20 years and the help of several assistants to make.

Adorning the main stairwell of the National Palace on approximately 1,200 square feet, the mural’s detailed scenes of monumental moments in history are some of the main reasons visitors come to the vibrant Zócalo, the city’s main town square.

Upon entering the stairwell, to the right is the first panel, “The Legend of Quetzalcoatl,” which chronologically begins the series of three. Casting the region’s Aztec origins in glowing and vibrant hues, the panel’s simplicity in color and composition communicates a time when all was supposedly harmonious.

To continue reading Mexico’s history, viewers crane their necks upward to take in the sights of conquest, enslavement, invasion, revolution and reform in the middle panel. It’s on this panel that one of the most important visuals of Mexican legend—the eagle holding a serpent—is central. Guides are also happy to point out key figures from the country’s history, including Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés, priest Miguel Hidalgo, Mexican Revolution leader Emiliano Zapata and more. The left-hand wall shows the early 20th century industrialization and is titled “Class Struggle.” It’s the artist’s most personal and politically charged message to his modern-age city: a hopeful vision of overcoming differences.

‘Transport and Human Endeavor’

By Edward Trumbull (1930), Chrysler Building, New York City

Edward Trumbull, one of the hardest-working muralist painters of his time, is the creator of a great, enduring piece of work depicting industrial America. To see his interior ceiling mural, visitors elbow in among office workers on the ground floor of this famous 77-story building that defines the New York City skyline. Entering through the Chrysler Building’s spectacular entrance of black granite and stainless steel, viewers behold the lobby of the 1930 art deco structure, with its walls and floors of exotic marble, ornate elevator doors and Trumbull’s mural above.

“It is really part of the fabric of the building and is such a rich narrative of the time that it was built,” says Bill Mensching, vice president and director of murals at EverGreene Architectural Arts, the elite team of art restorers that breathed new life into the mural in 1999. “Here was this art deco painting that glorifies the craftsman and laborer as a heroic figure advancing industry and progress, a theme that repeated in murals throughout New York City. At the same time, it pays homage to the modern ‘skyscraper’—a building form that had just started to define New York City.”

Trumbull, who was born in Michigan but a longtime resident of Pittsburgh, Penn., honed his traditional techniques when studying in New York and London, and painted both private and public service buildings throughout his career.

“Transport and Human Endeavor” is laced with gold leaf and surrounded by bold art deco patterns, and was painted on canvas before it was affixed to the ceiling. In the 1970s, a polyurethane coat was applied as a cheap varnish, and 24 recessed downlight fixtures were literally cut into the mural.

“Polyurethane can often do irreversible damage to oil paintings, and developing a protocol to remove the varnish without damaging the original surface took a great deal of time and testing,” Mensching says. “Although the holes weren’t huge, they really impacted some of the most important portions of the mural.” Now patched up and brightened, it’s a masterpiece on display.

‘Whaling Walls’

By Wyland (from 1981 – 2008), throughout Orange County, Calif.

When Wyland, often called the “artist of the sea,” set out to paint his first life-size public seascape and sea life mural in Orange County in 1981 at the age of 25, it took him two years of bureaucratic hurdles and listening to naysayers who were hesitant about public art.

“The idea was to take nature, put it in the context of an urban area, and remind us that this is part of the world we share,” Wyland says. “While we are driving in our cars or working in office buildings or building things in factories, there is an entire ecosystem co-existing along with us.”

Today, as he operates the nonprofit Wyland Foundation, various Wyland galleries around the United States and appears on the Discovery Channel, he continues to explore ways to support the environment, including the National Mayor’s Challenge for Water Conservation. In Orange County, when one sees the color blue, the mind goes to Wyland, who has four murals on view in close proximity: “Gray Whale and Calf” (Laguna Beach, 1981); “Young Gray Whale” (Dana Point, 1982); “Laguna Coast” (Laguna Beach, 1987); and “Pacific Realm” (the interior ceiling of Wyland Gallery, Laguna Beach, 1996).

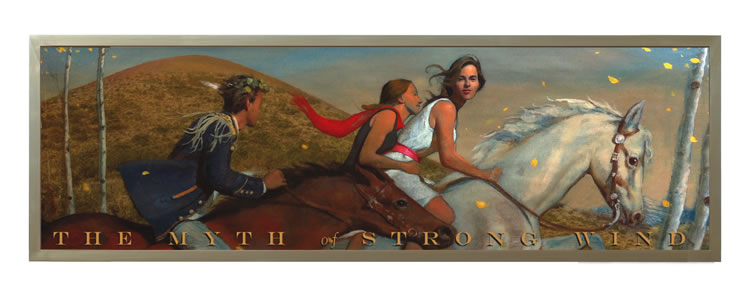

‘Strong Wind: The Myth of the Aspen Trees’

By Bo Bartlett (2013), The St. Regis Aspen Resort, Aspen, Colo.

A sense of calm movement as Aspen trees rustle in a mountain breeze emanates from Bo Bartlett’s new mural, which debuted in December 2013 at The St. Regis Aspen Resort. The piece, which is the eye-catching focal point of the Shadow Mountain Lounge, takes its narrative from a Native American folk tale that tells of a young warrior looking for true love. The tree’s signature eye-shaped markings are repeated throughout the stunning composition.

Bartlett started by spending a significant amount of time in Aspen getting to know the resort and the community. He created several iterations of composition studies, incorporating color palettes that accent the lounge’s mood, and then worked for more than a month on the mural canvas in his Georgia studio. As one of America’s most renowned realist painters working today—Bartlett’s work can be seen at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art and the Seattle Art Museum, among many others—his Aspen masterpiece is a modern interpretation of a mythological narrative.

In the “Strong Wind” folk tale, a young girl who is pure of heart wins the warrior’s hand. In his initial proposal, the artist stated, “The thing that touched me most about this myth is its similarities to, and differences from, the more familiar ‘Cinderella’ story. But, ‘Strong Wind’ is a consciousness-raising morality tale. … It’s all about seeing.”

Whether it’s a work steeped in history or one just created, there is no denying the powerful resonance of hand-painted art on a grand scale.

“I think that murals really speak to us across generations, telling the stories of their time … and are part of the identity of a single place,” Mensching says. “When I think of New York City buildings, the first picture in my mind is often of the artwork inside, from grand artworks like those in Rockefeller Center, … the Empire State Building [and] the American Museum of Natural History rotunda to gems like the Maxfield Parrish ‘Old King Cole’ mural at [The St. Regis New York].”

Murals truly live beyond their years, linking viewers through a shared history and ongoing appreciation of an art form that is, in fact, for the people.

***

A Storied Tradition

Though it debuted fairly recently, the “Strong Winds” mural at The St. Regis Aspen Resort is actually part of a long history of hand-painted artworks displayed in the hotel group’s lobby bars worldwide.

It all began in New York City more than a century ago. In 1905, artist Maxfield Parrish was hired to paint the mural for St. Regis founder Col. John Jacob Astor IV for $5,000. Despite his personal religious beliefs that opposed alcohol, the pay was so generous that Parrish couldn’t refuse the task. The famous piece, “Old King Cole,” aptly depicts Old King Cole in an allusion to Astor, and found its first home at the bar at his 42nd Street hotel, The Knickerbocker. After The Knickerbocker was converted into an office building, the work went into storage before finding its way to The St. Regis New York in 1932—where it debuted with much success, thus launching the lobby bar mural tradition.