Houston visionaries of past and present helped shape the city into what we know and love today. – By Cynthia Lescalleet

What once began on a little more than 6,000 acres has now turned into a burgeoning city of shops, restaurants, universities, museums and more, with about six million residents across 600 square miles. This is the city of Houston.

What once began on a little more than 6,000 acres has now turned into a burgeoning city of shops, restaurants, universities, museums and more, with about six million residents across 600 square miles. This is the city of Houston.

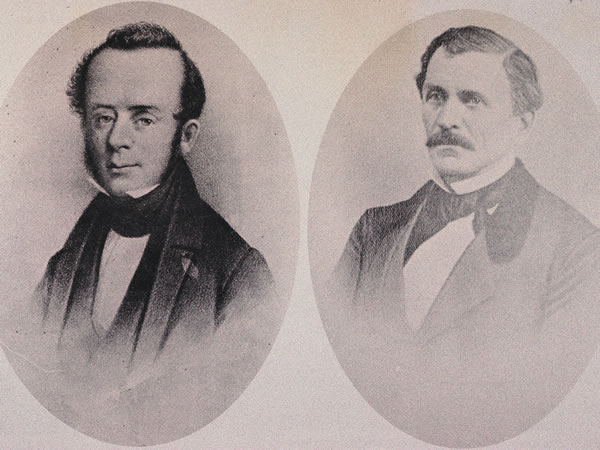

On Aug. 30, 1836, Houston was founded when Augustus Chapman Allen and John Kirby Allen, two brothers and real estate entrepreneurs who purchased the original land, ran an advertisement in the Telegraph and Texas Register for the “Town of Houston,” (named after illustrious political figure Sam Houston). They claimed that it would be the “great interior commercial emporium of Texas,” bragging that ships from New York to New Orleans could sail up the Buffalo Bayou, right to Houston’s front door.

Today, the city is the fourth largest city in the U.S. The Allen brothers, although a critical part of the Bayou City’s history, aren’t the only purveyors that have helped shape the booming cultural metropolis it has become today.

“We have a pattern of visionaries making the city what they wanted it to become,” says Jerry Wood, who serves as a demographics consultant for the city.

Some visions have been lofty, others a bit audacious. “Build it bigger, better or different has been a pervasive attitude,” says Betty Trapp Chapman, a Houston historian.

The Developers

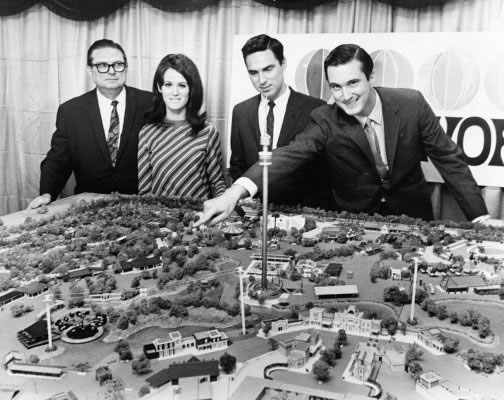

Former Mayor Roy Hofheinz championed the Reliant Astrodome, creating a standard on every domed stadium that followed, says Debbie Harwell, a University of Houston lecturer and Houston History magazine editor.

Similarly, developer Gerald Hines built the famously lavish Galleria in 1970, which boasts more than 375 stores and 24 million visitors each year. Additionally, Texas oilman Glenn McCarthy’s Shamrock Hotel on the outskirts of downtown defied naysayers. Razed in the 1980s, it attracted the midcentury jet set, celebrities and gala crowd.

“People still debate whether we should have torn it down,” Harwell says. The hotel and McCarthy’s personae—cowboy spirit mixed with oilman-wildcatter—represented Houston’s growth in those years, she adds.

Openness to ideas is as much a Houston trait as its blend of Southern and Western sensibilities. “They [business leaders] realized that they would succeed more easily if the town succeeded. That mindset became a characteristic of Houston,” Chapman adds.

The Futurists

The devastating “Great Storm of 1900” and the discovery of oil at Spindletop, east of Houston, set the city on its modern course, says John Boles, a Rice University history professor. The devastating storm wiped out nearby Galveston’s well-established port, shifting trade to Houston’s, which was smaller and served by a shallow channel in need of deepening. In completing Houston Ship Channel in 1914, a civil engineering feat, Houston and its port grew with nascent energy industry, Boles explains.

“There would be no deepwater port at Houston had it not been for the genius of Tom Ball,” says Jim Edmonds, chairman for the Port of Houston Authority Commission. Ball, who served on the port commission’s general counsel, pitched to U.S. Congress that Houston help pay for its port project. In due part, the Port of Houston became home to one of the world’s largest petrochemical complexes. It leads U.S. ports in foreign tonnage and ranks second in overall tonnage.

In education, forward-thinker Edgar Odell Lovett, first president of Rice Institute (now Rice University) believed “all great cities need a great university,” Boles says. “Lovett took what was a vague charter and shaped it into something concrete.” His bold vision was for Rice to be a great research university—right from its start a century ago this year. Currently, Rice has about 4,000 undergraduates enrolled and is considered one of the elite universities in the U.S.

The Investors

Whether Houstonians by birth or by choice, a core of early civic leaders shared the attribute of generosity, Harwell says. “They were dedicated to making Houston a pleasant and productive environment. They were personally committed, invested in the city.”

During the early 20th century, business titan Jesse Jones’ mark was wide and literally high, as an industrious builder who transformed Houston’s early skyline. Also a newspaper publisher, banker and national public servant, Jones marshaled the private sector’s support of Houston Ship Channel.

Gus S. Wortham built insurance giant American General and was considered astute at networking to realize his visions. He and wife Lyndall Wortham financially supported the performing arts, city beautification and scientific research, as does The Wortham Foundation they established.

The beloved Hermann Park, which welcomes 6 million visitors each year, takes its name from industrialist George H. Hermann. He gave the city 285 acres for a park, and upon death, bequeathed more city land and money for a charity hospital. Thus, Hermann Hospital opened in 1925 and was the first hospital to join the Texas Medical Center (TMC), chartered two decades later.

The Culturalists

For sheer cultural impact, Ima Hogg embodies vision and leadership in civic philanthropy, says Bonnie Campbell, director of Bayou Bend Collection and Gardens at Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (MFAH).

“She not only anticipated but helped shape and champion many important 20th-century ideas that impacted citizens during her lifetime and beyond,” Campbell says. Among them: green space, music appreciation and preservation of national, state and local heritage. Her world-class collection of American paintings and artwork was a gift to MFAH, as was her mansion on 14 acres, now an MFAH estate.

Art collectors Dominique and John de Menil introduced Houston to modern art and architecture, later opening the idyllic gallery and campus of The Menil Collection. Also, by tapping architect Philip Johnson for local projects, they shaped a relationship among the architect, developer Gerald Hines and the Houston skyline.

Impresario Edna Saunders was a leader of Houston’s cultural development. Before the city had its own resident companies in theater, dance, symphony and opera, Saunders brought in the world’s best to perform. “She developed the appreciation that led to the development of what we have today,” Chapman says.

Nina Vance founded and led the Alley Theatre, established its national reputation and spearheaded fundraising to realize her goals for it. “Nina Vance envisioned a professional theater company performing in its own downtown building with two stages,” explains Dean R. Gladden, Alley Theatre’s managing director. Opened in 1968, the Alley is one of the few remaining American theater companies with a professional resident acting company year-round.

From key developers to business barons and cultural titans, these futurists had a vision for their beloved city. Without them, Houston wouldn’t be rooted in the strong culture that we all know and love today.