Ferrying in the Trend

The San Francisco Ferry Building launched a major food movement and continues to set the stage for fresh, organic and local flavors.

By Tiffany Maleshefski

Before it became the majestic, unmistakable landmark it is today, the Ferry Building first opened its doors to the world in 1875 and was simply called the Ferry House. The structure was made of wood and was the primary point of arrival and departure for San Francisco, prior to the erection of the Golden Gate and Bay bridges. In 1894, local architect A. Page Brown was commissioned to erect an entirely new building.

Brown, who oversaw the construction of the city’s stunning Grace Cathedral, designed the gorgeous Beaux Arts building and the signature 245-foot tall clock tower that stands there today. In its heyday, the Ferry Building serviced more than 100,000 passengers every single day. But as more people started to jump in their cars and traverse the San Francisco Bay via its two bridges, ferry service began dropping off and was eventually discontinued in 1967, and quickly thereafter the building fell into disrepair. In 1998, the nationally registered historic landmark got a second chance when it underwent a massive four-year renovation.

Brown, who oversaw the construction of the city’s stunning Grace Cathedral, designed the gorgeous Beaux Arts building and the signature 245-foot tall clock tower that stands there today. In its heyday, the Ferry Building serviced more than 100,000 passengers every single day. But as more people started to jump in their cars and traverse the San Francisco Bay via its two bridges, ferry service began dropping off and was eventually discontinued in 1967, and quickly thereafter the building fell into disrepair. In 1998, the nationally registered historic landmark got a second chance when it underwent a massive four-year renovation.

One of the most notable outcomes of the building’s rehabilitation was the transformation of the building’s ground floor, originally the baggage area, into a 65,000-square-foot gourmet marketplace. When the building reopened in 2003, it was reborn as a bustling marketplace, chock-full of new vendors that emphasized products made locally and from sustainable methods. It also kicked off one of the most successful farmers markets in the country, offering certified organic products and produce, and drawing more than 25,000 shoppers every week.

One of the most notable outcomes of the building’s rehabilitation was the transformation of the building’s ground floor, originally the baggage area, into a 65,000-square-foot gourmet marketplace. When the building reopened in 2003, it was reborn as a bustling marketplace, chock-full of new vendors that emphasized products made locally and from sustainable methods. It also kicked off one of the most successful farmers markets in the country, offering certified organic products and produce, and drawing more than 25,000 shoppers every week.

Suddenly, the rebirth of the Ferry Building represented a lot more than simply a historic building saved from ruin. Instead, it became a beacon for a national movement seeking to better educate consumers on where their food comes from and encourage them to support local food purveyors as much as possible.

Farm to Restaurant

While the Ferry Building has started something of a food revolution for consumers, for chefs these lessons are ones they’ve embraced for decades. The Ferry Building, however—and its farm-to-table mantra—has been instrumental in helping San Francisco chefs truly illustrate that concept by linking what happens at the farm to what appears on their tables.

At Vitrine, St. Regis’ casual dining spot, Executive Chef Romuald Feger, builds his menu around seasonal, locally grown ingredients. And while many are choosing to see what he and so many other chefs are doing as a “trend,” he sees it as an old concept that the mainstream has simply forgotten.

“About a century (and perhaps not even that long) ago, we were local, fresh and sustainable by design,” he says. “People used to eat what was available in their country, area and field or garden because it was just impossible to ship vegetables, meats or fish around the world. At my level as a chef, it’s not so much a trend but rather a way of life.”

“About a century (and perhaps not even that long) ago, we were local, fresh and sustainable by design,” he says. “People used to eat what was available in their country, area and field or garden because it was just impossible to ship vegetables, meats or fish around the world. At my level as a chef, it’s not so much a trend but rather a way of life.”

Feger grew up in a small town in Alsace, France, with most of the family meals coming from a small farm owned by his grandparents.

“The only food they cooked was that which was available to them on the farm or at the market. Watching them was great. It was the first experience that exposed me to food early on,” Feger says. “In fall we used the harvest and the apple and pear for the winter. The apples we ate were far different from the ones you find in the supermarket. They were not perfectly round or red, but how tasty and sweet they were regardless! A granny smith, gala or golden apple could not compare.”

That upbringing has instilled in Feger a desire to seek the best produce possible in preparing any dish. Fortunately, being in the Bay Area means he doesn’t ever have to search too far. The Ferry Building, and its range of purveyors, helps local chefs to create menus that showcase the diversity of the Bay Area’s food scene and helps visitors get to know the area.

“The fresh produce market taking place every Saturday at the Ferry Building is a window into what the Bay Area has to offer in terms of food,” he says. “I believe that the best way to understand a city, a place and a country is through exploring such open markets. These types of markets are the pulse of the season; places where you can touch, try, see, smell and discover what nature has to offer.”

Chef Feger’s personal favorites at the Ferry Building: “The fresh produce market on Saturdays, Cow Girl Creamery for the cheese, Boccalone for the artisan meats, Recchuiti for the chocolate and Acme Bakery for the bread.”

Chef Feger’s personal favorites at the Ferry Building: “The fresh produce market on Saturdays, Cow Girl Creamery for the cheese, Boccalone for the artisan meats, Recchuiti for the chocolate and Acme Bakery for the bread.”

“The Ferry Building has been a great asset to us,” says Brenna Schlagenhauf, spokeswoman for the Hog Island Oyster Co. “We’re able to reach out to a group of clients in the Bay Area and who are traveling through the Bay Area who might not get up to our farm in Tomales Bay.”

Located in Marshall, Calif., the family-owned farm leases 160 acres in Tomales Bay and raises 3 million oysters, manila clams and mussels every year. In 2013, the business will celebrate its 30th anniversary. Hog Island is nationally recognized as one of the country’s premier oyster farms. Great care is taken to see to it that the shellfish are raised and harvested in the least stressful conditions possible. All shellfish is sorted by hand, and after oysters are harvested, they are put in wet storage tanks. Water from Tomales Bay is piped into these tanks and chilled to a refreshing 49 degrees.“It’s like an oyster spa,” Schlagenhauf says.Hog Island is actively involved in protecting and restoring the Tomales Bay watershed and has been identified as “Super Green” by the Monterey Bay Aquarium, a rating given to seafood purveyors who raise seafood that is deemed healthful and does not harm the oceans.

Located in Marshall, Calif., the family-owned farm leases 160 acres in Tomales Bay and raises 3 million oysters, manila clams and mussels every year. In 2013, the business will celebrate its 30th anniversary. Hog Island is nationally recognized as one of the country’s premier oyster farms. Great care is taken to see to it that the shellfish are raised and harvested in the least stressful conditions possible. All shellfish is sorted by hand, and after oysters are harvested, they are put in wet storage tanks. Water from Tomales Bay is piped into these tanks and chilled to a refreshing 49 degrees.“It’s like an oyster spa,” Schlagenhauf says.Hog Island is actively involved in protecting and restoring the Tomales Bay watershed and has been identified as “Super Green” by the Monterey Bay Aquarium, a rating given to seafood purveyors who raise seafood that is deemed healthful and does not harm the oceans. And it ’s important to Hog Island that its methods and commitment to sustainability is conveyed to the thousands of people who enjoy their oysters at the Ferry Building location. That’s why all staff that work at the Ferry Building undergo intensive training throughout the year.”All of the staff gets education training by our co-founder … so everyone is educated on our process of farming,” Schlagenhauf says. “If you visit us in San Francisco, you can have a conversation with our services, shuckers, et cetera, who can share how we develop our product and certain aspects of the company.”

And it ’s important to Hog Island that its methods and commitment to sustainability is conveyed to the thousands of people who enjoy their oysters at the Ferry Building location. That’s why all staff that work at the Ferry Building undergo intensive training throughout the year.”All of the staff gets education training by our co-founder … so everyone is educated on our process of farming,” Schlagenhauf says. “If you visit us in San Francisco, you can have a conversation with our services, shuckers, et cetera, who can share how we develop our product and certain aspects of the company.”

Where’s the Beef?

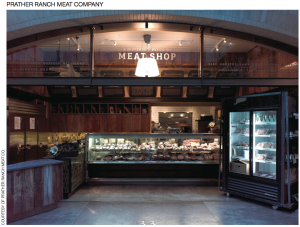

Similarly, Prather Ranch Meat Co. which sells dry- aged beef, heritage breed pork and lamb, American bison and local poultry, has used its presence there as an opportunity to teach and educate consumers about its sustainably ranched meat.

It has been in the Ferry Building since 2003, and in 2011 doubled the square footage of its retail operation. The store sells sustainably ranched meat from several different ranches, with its beef coming exclusively from Prather Ranch, a 40,000- acre cattle ranch and farm located near Mt. Shasta. The ranch operates a closed herd, certified organic and humane farm. While people are invited to visit the farm, the retail operation in the Ferry Building is much more convenient.

“We wouldn’t sell anything we wouldn’t serve to our children and grandchildren,” says Mary Rickert, one of the ranch’s general managers.

While people are welcome to visit the farm that’s located more than 300 miles away from San Francisco (and they do), it’s much easier to get their message across to the hundreds of thousands of people who visit the Ferry Building every year than it would be to get all of those people up to their ranch.

“The Ferry Building has lots of opportunity for consumer education,” Rickert says. She hopes that eventually vendors like her will be given the chance to invite the men and women who work the farms, herd the cattle and shuck the oysters to speak at the Ferry Building.

“The Ferry Building has lots of opportunity for consumer education,” Rickert says. She hopes that eventually vendors like her will be given the chance to invite the men and women who work the farms, herd the cattle and shuck the oysters to speak at the Ferry Building.

“I want to forge a better link between the retail outlets and the supplying farms,” she explains.

Beyond the Farm

Beyond the Farm

When most people think of the fish and farm- to-table movement, they tend to only think of produce, fish and meat, but the Ferry Building showcases everything in between as well.

After developing a loyal following at the Ferry Building’s farmers market, Jacky and Michael Recchiuti, the husband and wife team behind Recchiuti Confections, were invited to open their truffles and confection shop inside in 2003. Folks flock to the luxury chocolate shop, gobbling up their sweets. The chocolate shop also furthers the overall message of sustainability, but goes beyond farm to table, advocating sustainability even in its packaging.

“Although a small portion is mechanized, we are still very much an artisan hand-made confection maker,” explains Michael Recchiuti. “We use traditional European-style methods of incorporating flowers (lavender) and herbs (lemon verbena) from Eatwell Farms out of Dixon, Calif. Tarragon is from Mariquita Farm; the dairy we use is local. Our boxmaker is local and not outsourced overseas, so our packaging has a percentage of post consumer/recycled paper used within.”

What was revolutionary in 2003 is now very much the norm in San Francisco, so the next challenge among its purveyors and the local chefs who partake in its bevy of fresh and diverse products is to grow the movement across the United States, something that will be no easy feat. But as more cities and communities encourage the growth of farmers markets, the educational lessons that the Ferry Building has successfully imparted to San Francisco and its many visitors can and will be taught to the generations ahead.

“Time has gone by and a lot has changed,” chef Feger says. “Cities are concentrated with more people than ever. We connect less and less with nature and our agendas are overbooked. Most of the time, a couple is working and they don’t spend much time around a table, much less in the kitchen to cook a whole dinner. If parents don’t take the time to teach their kids, take them to the market or cook for themselves at home, the kids will never be able to know the difference. What’s more, they won’t know what is available or what exists in nature and further down the line, won’t be able to educate their kids.”

CHEF ROMUALD REFER’S THREE REASONS TO SHOP LOCAL

1. Everything from fruit to cheese has a “season” or a right time to be eaten, and if you follow that simple rule, then you are sure to eat your food at its very best. Would you enjoy having a Christmas tree year-round in your living room? Probably not! and the same applies to most of what we eat. This reminds me of one of my chefs who also used to say that an item “is always in season somewhere in the world.” he wasn’t completely wrong, but what an odd way to explain why we had asparagus on the menu year-round!

2. Fruit and vegetables are shipped from around the world. if produce is not fresh, seasonal and local, you’re faced with products developed through types of agricultural research that can develop and select species that have a better shelf life, grow faster or are easier to expedite over a long distance. The result is less taste, sugar, vitamins, nutrients and variety.

3. Also, in using seasonal, local ingredients, you keep the community in your area alive and employed.