The era of classic Hollywood cinema produced some of the industry’s most timeless and memorable films, paving the way for the future of filmmaking.

By Peter A. Balaskas

From the late 1920s to the early 1960s, Hollywood experienced a creative and technological boom in the film industry that is now known as the Golden Age of Hollywood cinema. This distinctive period was a simpler—and more private—time in Hollywood, when actors such as Cary Grant, Spencer Tracy, Grace Kelly and Joan Crawford were symbols of class and glamour. Moreover, directors such as John Ford, Frank Capra, William Wyler and Alfred Hitchcock were the captains of their cinematic ships, and the studios were the masters over every movie produced. Although the Golden Age slowly reached its end in the early 1960s, the films during that celebrated era, as well as the stars and filmmakers who created these masterpieces, still possess a rare type of longevity that continues to resonate in the memories of movie lovers around the world.

Cinematic Landmarks

Frank Capra’s 1934 classic “It Happened One Night” (starring Clark Gable and Claudette Colbert) was the first of three films to sweep the Big Five Oscar categories (Best Picture, Actor, Actress, Director and Screenplay).

First coined by film historians David Bordwell, Janet Staiger and Kristin Thompson during their study of Hollywood films between the years 1917 to 1960, the classical Hollywood narrative style is the most commonly used technique in filmmaking today and was seen in some of the most iconic films during the Golden Age.

“The classic studio era … is a time period where the great motion picture studios were most consolidated and basically operated a monopoly of the industry,” says Jan-Christopher Horak, director of the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) Film & Television Archive. “That studio system developed a very particular aesthetic of filmmaking, which we call the classical Hollywood narrative style.”

Horak elaborates that this specific style of filmmaking involves the basic storytelling narrative (utilizing a beginning, a middle and an end) and that the story is filmed and edited in such a way that the viewer is immersed in a “quasi-real experience.” He also emphasizes the importance of larger-than-life characters, which serve as valuable assets for this classical Hollywood style.

“The whole notion was that there would be no artifice and that the audience would literally, through identification with characters, be sucked into the narrative and not be aware of the fact that they are actually watching a film,” he explains. “It’s a style [that] is completely unselfconscious.”

Throughout this Golden Age, Hollywood cinema showcased the highest quality of films that often reflected significant moments in American history. Depression-era films of the late 1920s gave birth to Charlie Chaplin’s “The Gold Rush” (1925) and “The Devil’s Circus” (1926), as well as the World War I production “Wings” (1927, Gary Cooper), which was the first film to win an Academy Award for Best Picture. Westerns, adventure epics and gangster films rode briskly through the 1930s, including “Little Caesar” (1931), “The Public Enemy” (1931) and “The Adventures of Robin Hood” (1938).

But it was 1939 that became the most creatively prolific year for that decade, showcasing classics such as “Stagecoach,” “The Wizard of Oz” and “Gone with the Wind,” which was the first color film to win the Best Picture Academy Award.

The 1940s were popular with groundbreaking classics such as Citizen Kane (1941) and “It’s a Wonderful Life” (1946) and gritty film noir masterpieces like “Double Indemnity” (1944) and “The Big Sleep” (1945). A dark genre, 1940s film noir cinema set the stage for a new type of protagonist and a new type of villain: the anti-hero and the femme fatale.

“Hollywood made itself a magnet for cinema talent throughout the world,” says film historian Jonathan Kuntz, who also serves as visiting professor at the UCLA School of Theater, Film and Television. “Almost every major filmmaker ended up doing something for Hollywood in that period. And, of course, it was the glamour capital, you might say, of the world.”

The directors of the Golden Era, including John Huston, Frank Capra, Howard Hawks, Ernst Lubitsch and Orson Welles, became cinematic pioneers. But, as Horak says, Hollywood particularly welcomed international directors.

“After the rise of Hitler in Germany, you [had] several hundred filmmakers from Berlin, Vienna and Budapest leaving central Europe and coming to Hollywood,” he says. “That was a much bigger influence on things. And so something like film noir, for example, is very strongly influenced by those filmmakers, people like Billy Wilder, Otto Preminger and Fritz Lang.”

The Studio System

Although the stars had the spotlight, it was the studios that literally had complete ownership of the entire film industry. All artists—actors, directors and craftsmen—were bound to their studio employers with multiyear contracts, ranging from seven to 20 years. But the key factor for the major studios—also known as the Big Five (MGM, Warner Bros., RKO Pictures, Paramount Pictures and Fox Film Corp.)—was their multifaceted ability for vertical integration.

During World War II, many Hollywood artists, including Clark Gable, Jimmy Stewart and Henry Fonda, had to go on hiatus from their film work when they served in the armed forces.

“They controlled the market from the moment of inception to [the films] being shown on the screen,” says Horak, adding that it was a three-tiered monopoly where they served as producers, distributors and exhibitors, including having complete ownership of all their theater chains. This studio system process increased film production with approximately 300 films being released each year (50 films per major studio).

Despite increased film production, there were two reasons why the studio system ended. The first was the enactment of the Paramount consent decree of 1948, which forced all the studios to sell off their movie theater chains and focus only on production anddistribution. As a result, each studio would have to compete in the theater marketplace for every feature that they produced.

The second reason was the advent of American television, which took mass audiences away from the movie theaters. This resulted in a steady decrease at the box office until it bottomed out in 1963, the worst year for American film production in the past 50 years. The actors, directors and craftsmen were now free agents, responsible for their own successes.

Unforgettable Stars

When it came to the actors of Hollywood’s Golden Age, people arrived to the movies in droves to see legends such as John Wayne, Gary Cooper, Rita Hayworth, Ingrid Bergman and Betty Grable, to name a few.

“The stars were wonderful because we connect with them and we see them in other films, and we notice … something about them,” says Kuntz, who also believes that this longevity was due to the marketing and publicity methodologies of the studio system that increased their popularity.

“Many of [the stars] had been made by the studios,” he continues. “They had a whole star-making apparatus. Of course, they loved it when super talented people came along. But they needed far more stars than they had super talented people.

So, they were constantly bringing up young, relatively little-known people and turning them into stars and keeping them [in] long-term contracts.”

Marlon Brando was one of five actors who was nominated for an Oscar four consecutive times.

During the Depression era (late 1920s to 1930s), Broadway stage and radio artists such as Bette Davis, James Cagney and Clark Gable were the must-see stars. With the coming of World War II and postwar cinema (1940 – 1949), the new stars included the likes of Robert Mitchum, William Holden and musical performers Gene Kelly and Judy Garland. But many of the stars from the 1930s strengthened their marketing presence into the next decade, most notably Oscar-winning actor Humphrey Bogart.

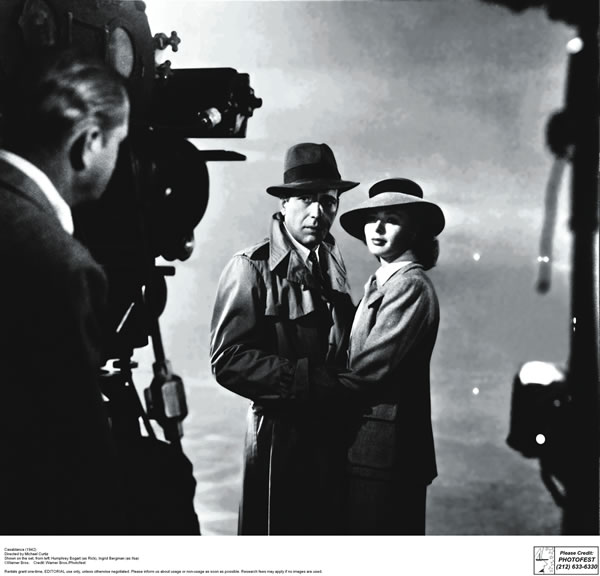

“Humphrey Bogart becomes a fascinating star in the 1940s,” Kuntz explains. “[He’s] a tough guy who mostly played villains in the ’30s. But by the 1940s, he’s perfect for this new kind of tougher, maybe ‘badder,’ good guy that we see beginning with ‘The Maltese Falcon,’ ‘High Sierra’ (both in 1941), and then of course peaking with ‘Casablanca’ (1942), where he plays the disillusioned salon keeper who ends up committing himself to the allied cause.”

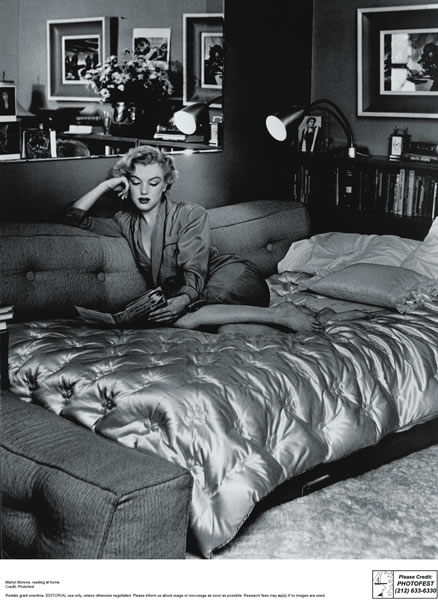

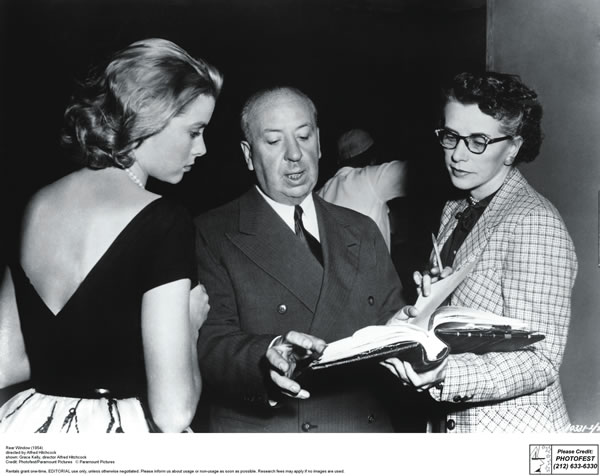

As Hollywood’s Golden Age came closer to an end in the 1950s and 1960s, it also brought about a period of biblical and historical epics (“Ben-Hur,” 1959; “The Ten Commandments,” 1956), John Ford and John Wayne classic collaborations (“Rio Grande,” 1950; “The Quiet Man,” 1952; and “The Searchers,” 1956) and Alfred Hitchcock thrillers (“Rear Window,” 1954; “North By Northwest,” 1959; and “Psycho,” 1960). The era also introduced the appearance of the notorious method actors—those who brought a sense of realism into the storyline—which included Paul Newman, Marlon Brando, Steve McQueen, Montgomery Clift and Marilyn Monroe.

“There was this new generation of performers who got inside their characters, who allowed themselves to appear imperfect on screen, nervous and troubled,” Kuntz says. “And so we had that wonderful generation.”

Preserving the Golden Age

Like their stars, the films of the Golden Age have transcended time and maintained their appeal with future generations of filmmakers and film lovers alike.

“Modern filmmakers are very film history savvy,” Kuntz says. “They know where their roots are, and so a lot of modern filmmakers have a great appreciation, particularly for the filmmakers of their youth.”

In terms of why these classics sustain their immortality, it all comes down to good storytelling and the moviegoers that they connect with.

“The films were made to be appealing to the mass audiences then,” he continues. “So it’s not surprising that at least parts of the mass audience of today still love them. In many ways, [the Golden Age] is deeply connected to the entire country throughout the 20th century. And so, if you are an American, or like America, you see … a lot of the best side of 20th century America in the classic Hollywood films.”

Whether learning cinema education at film schools or hosting a classic movie marathon at home, the Golden Age of Hollywood captivates the hearts and souls of film aficionados around the world. But these classic cinematic tales and their magnetic, glamorous stars also possess the uncanny ability to seduce those who are unfamiliar with this poignant era.

As long as they still exude their mystique and timelessness, the films of Hollywood’s Golden Age will continue to be immortalized for future generations yet to come. B