The Cowboy Mystique

With the taming of the Western frontier, the Texas cowboy evolved from a rugged individualist to an American icon.

By Cindy Hale

In the early 1700s, land grants from the Mexican government allowed American colonists to homestead on what is now southeastern Texas. Albeit comfortable on horseback and familiar with animal husbandry, these early ranchers were unprepared to manage the longhorn cattle that roamed the grasslands.

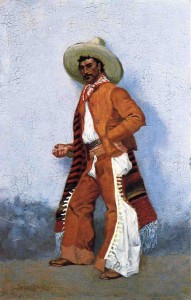

With horns that measured 4 to 8 feet across, the longhorns were a powerful breed. Brought north from Mexico to sustain the efforts of evangelical Catholic missionaries, the longhorns were scrappy and ferociously feral. Fortunately the Mexican vaqueros proved to be gracious mentors. Within a short time the nascent cowboy had mastered lassoing techniques as well as a more dynamic style of horsemanship. In fact, the American cowboy’s tack and apparel, from saddle and lariat to hat, chaps and boots, were inspired by the vaquero tradition.

Have Saddle, Will Travel

gracious mentors.”

At that time, the cowboy culture on a larger scale held little allure. Without any reliable means of long distance transportation, butchered meat spoiled quickly. Profits from cattle ranching only came from hides and tallow, which were shipped to distant markets via ports in the Gulf.

It wasn’t until the California Gold Rush that Texas ranchers finally viewed cattle as a potential moneymaking venture. The onslaught of the ’49er prospectors—and the gold investors who tagged along—bolstered the growth of commerce centers like San Francisco. A populace hungry for meat on the hoof was too tempting to ignore. Eying profitability, ranchers gathered herds of cattle and entrusted their cowboys to usher their stock further west. The trip to California, where cowboys coaxed and coerced cattle through arid wastelands, mountainous passes and Indian territories took about five months. It was a task laden with dust, cactus, rocks and endless boredom, punctuated by intermittent periods of panic instigated by the occasional stampede. Crossing water was particularly dangerous, and drowning was just as likely a cause of death for a cowboy as being tossed from a horse or trampled by a rampaging steer.

Back on the ranch a cowboy could expect steady wages, regular meals and a roof over his head in the bunkhouse. When personalities clashed, a cowboy could just pack his saddle bags and take his considerable talents elsewhere; ranchers were always in need of another “top hand.” This tendency toward a vagabond lifestyle colored the cowboy as just another fellow making his way on the vast frontier, albeit in a way that (hopefully) kept him out of the local hoosegow. That perception was altered once the transcontinental railroad chugged its way across the plains in 1869.

Trails to Rails

The opening of the railroad meant that cattle raised in the southwest could be shipped elsewhere in the form of meat on the hoof. All the ranchers had to do was get their livestock to the train on time. Thus began the era of the great cattle drives through Texas, where 2,000 or more head at a time were escorted along established routes like the famed Chisholm Trail to the railroad yards in Kansas. Each trip took about 100 days and required the work of about 20 cowboys. Yet the job was hardly lucrative for them.

The trail boss, who wielded supreme authority, typically earned $100 per month. Next on the pay scale was the chuck wagon cook, who had the potential to make the journey sufficiently tolerable or a living hell, depending on his culinary talents (or lack thereof). He earned about $60 per month. The average cowboy, who spent up to 12 hours a day in the saddle, was paid half of that. It was a grueling, dusty endeavor. Fortunately, the need for marathon cattle drives came to an end in the 1880s once trains, complete with refrigerated boxcars, trekked farther into Texas.

Beyond transporting cattle, the railroad deserves credit for contributing to the cowboy mystique. Trains delivered writers and artists to the frontier’s doorstep, each one eager to document their interpretation of the frontier.

Most of that period’s Western literature is more appropriately classified as pulp fiction. Similar in theme to Europe’s “penny dreadfuls,” America’s dime novels presented a gallant protagonist—incarnated as a gallant cowboy—who overcame challenges like gunslingers and renegade Indians to rescue the heroine or otherwise save the day. Readers back East and in Europe were captivated by these hyperbolic yarns and devoured them voraciously. Thus the mythology of the rugged yet chivalrous cowboy was born.

Meanwhile artists portrayed the Western landscape in all its brutal beauty, evoking romantic notions toward the untamed panoramas. The cowboys who populated these scenic images became symbolic of the self-reliant individualist, defiant in the face of adversity. Charles Russell and Frederic Remington are undeniably the most esteemed among these artists. While Russell often concentrated on the life of the working cowboy, Remington focused on dynamic depictions of cowboys locked in combat, whether the foe was an outlaw, a renegade Indian, a bronc or Mother Nature. Ultimately, though, both Russell and Remington idealized the cowboy as a heroic everyman, whose commonsense intellect and unwavering spirit allowed him to survive in the uncivilized West.

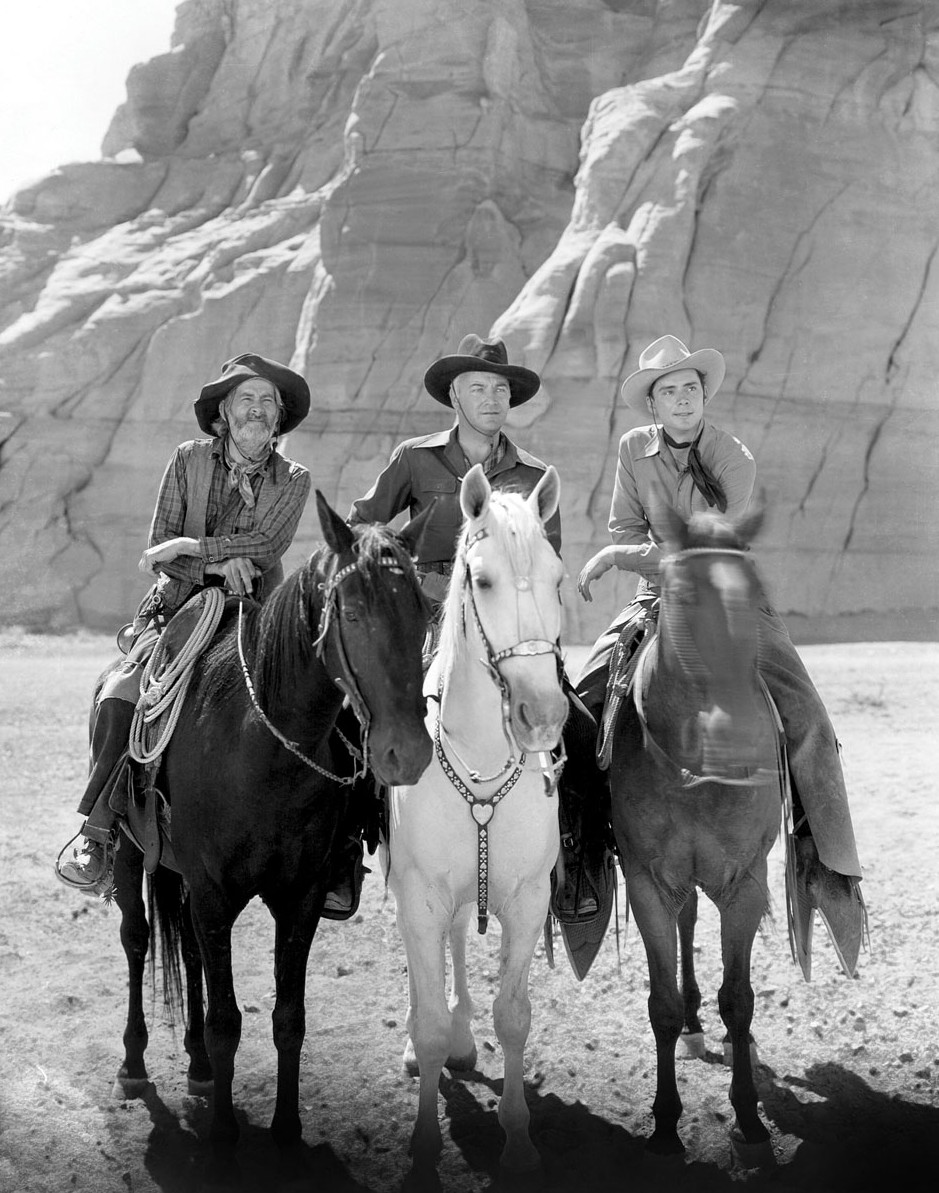

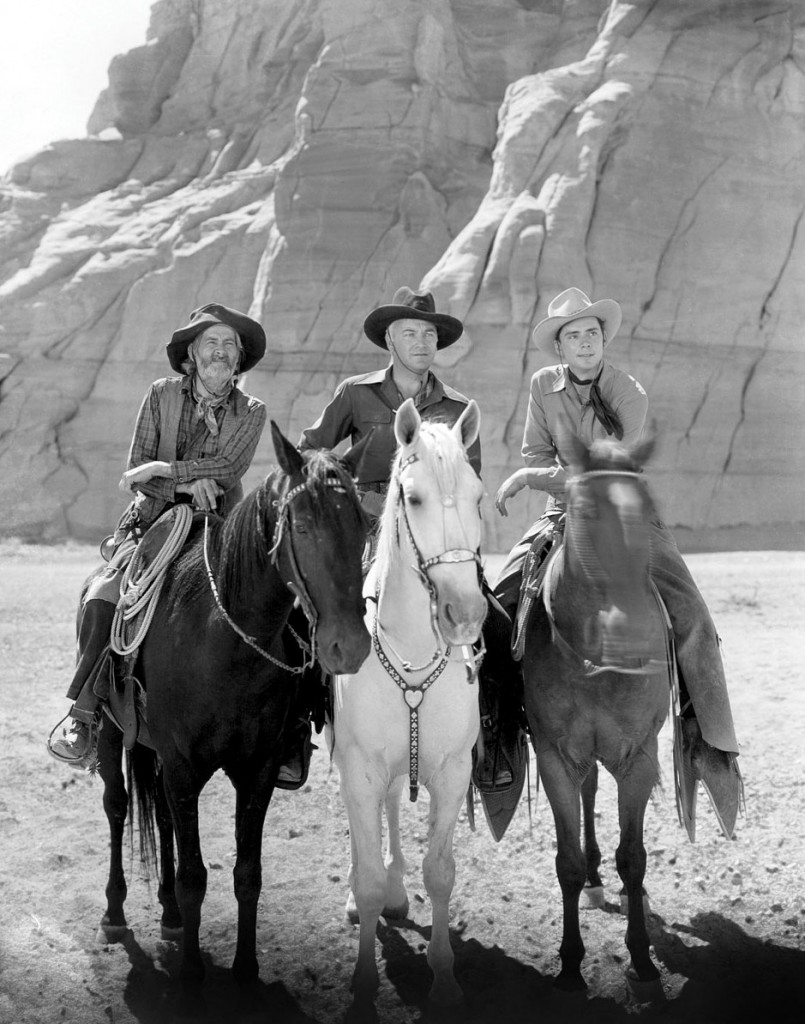

Though Texas and the frontier were soon to be tamed, Americans held fast to the cowboy as a revered icon. Even Hollywood’s first pantheon of stars was populated with cowboys such as Tom Mix, Gene Autry, Hopalong Cassidy and Roy Rogers. In remembrance of the hardy fellows who lived before them, these matinee role models embodied courage and tenacity while remaining beholden to women and their favorite horse. Thus, the cowboy mystique had become an integral aspect of American culture—despite that the Old West had long since ridden off into the sunset.

Revisit The Old West

George Ranch is only 30 miles from downtown Houston, but once through the gates you’ll be transported to a past era. The immaculately maintained park presents 100 years of Texas history by recounting the legacy of several generations of one pioneering family.

George Ranch is only 30 miles from downtown Houston, but once through the gates you’ll be transported to a past era. The immaculately maintained park presents 100 years of Texas history by recounting the legacy of several generations of one pioneering family.

The exquisitely restored buildings include the original 1830s homestead, a post-Civil War prairie home, a resplendent Victorian mansion and a 1930s ranch home. Related exhibits include a sharecropper’s farm, a chuck wagon camp and a blacksmith shop. Hands-on activities like weaving and harvesting in-season crops, plus costumed presenters and real-life working cowboys, add authenticity to your visit.

George Ranch gives a sense of what life was like “back then,” through sample meals prepared with old-time recipes. Offered only on Saturdays, the casual yet hearty lunches rotate among various sites, and menu reflects the venue. For example, the Chuckwagon lunch features beef stew and biscuits, while the prairie home lunch includes roasted chicken and apple pudding. The cost for these special meals is not included with admission to the park.

George Ranch is open Tuesday to Saturday from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. For the most rewarding experience, approach the homes and related exhibits in chronological order and plan to spend at least three hours in the park. Expect a bucolic setting perfect for a walking tour—albeit at the whims of Texas weather, dress accordingly. If you need a lift, convenient shuttles (tractor-pulled wagons) make frequent stops. (10215 FM 762 Rd., Richmond; 281-343-0218; georgeranch.org)

Cowboy Connections

Houston has undergone its own transformation into a thriving nexus of business and culture, yet it remains Western at heart. That means there are plenty of opportunities to embrace your inner cowboy (or cowgirl).

For upscale apparel visit Pinto Ranch, which features sportswear, business attire and special occasion fashions with a Western flair. A wide-range of boots handmade from exotic leathers also await you. Accessorize your look—or treat someone special—with Western-inspired jewelry crafted in gold, silver and precious stones by Esquivel and Fees. Since the studio is connected to the showroom, the designing duo is happy to make one-of-a-kind pieces according to your wishes. (1717 Post Oak Blvd., Houston; 713-333-7900; pintoranch.com)

Decorate your home or office with unique Western decor available at The Gallery at Midlane. Specialties include original artwork from members of the Cowboy Artists of America and a selection of re-envisioned frontier furniture. For more aesthetic treats, visit Houston’s Museum of Fine Arts, which is home to a small, eclectic collection of Remingtons and Native American art. (2500 Mid Ln. # 7; 713-626-9449; thegalleryatmidlane.com)

For the ultimate cowboy connection, saddle up at Cypress Trails Equestrian Center. Horses are available for guided rides along shady trails. The popular ride-and-tie excursion includes lunch at a secluded cafe. (21415 Cypresswood Dr., Humble; 281-446-7232; horseridingfun.com)

Or make plans to attend RodeoHouston. The annual extravaganza is more than a world-famous rodeo. Festivities include a carnival, barbecue cook-off, championship horse show and concerts with headliners like Brad Paisley and ZZ Top. (Reliant Center, 8334 Fannin St.; 832-667-1000; rodeohouston.com)