Summer at the de Young Museum presents a fresh crop of insightful shows.

By Jenn Thornton

Since its inception in 1895 as the Memorial Museum, intended to house exotic peculiarities for the California Midwinter International Exposition, the de Young Museum has been a cultural touchstone i

Since its inception in 1895 as the Memorial Museum, intended to house exotic peculiarities for the California Midwinter International Exposition, the de Young Museum has been a cultural touchstone i

n San Francisco and a beacon of the art world’s virtuosity beyond. Located in Golden Gate Park and one of two institutions that make up the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco (FAMSF)—the other being the Legion of Honor, a beaux-arts beauty in Lincoln Park—the de Young Museum has morphed into a leading institution for work in the realms of American art and ancient cultures.

In 2005, the de Young reopened in a gleaming new home—and did so most dramatically on its opening weekend, with 50,000 guests eagerly turning out to glimpse the new structure designed by noted Swiss architecture firm Herzog & de Meuron and Fong & Chan Architects in San Francisco. The museum’s striking, state-of-the-art facade and airy, open space within proved the perfect foil for not only the natural surroundings it complements, but also the progressive artistic thinking that the works inside continue to advance.

Today, the de Young continues to attract both art aficionados and casual viewers alike with its exclusive collections and rotating roster of engaging retrospectives, including several intriguing exhibits this summer.

One for the Books

When artist and poet Walasse Ting’s groundbreaking artist-illustrated book “1¢ Life” was published in 1964, it was “avant-garde in the extreme,” explains Colleen Terry, assistant curator of the Achenbach Foundation for Graphic Arts. The book, which brings together 61 poems by Ting and responses to these texts by 28 artists, serves as inspiration for the de Young’s bold ode to abstract expressionism, “A book like hundred flower garden: Walasse Ting’s ‘1¢ Life.’ ”

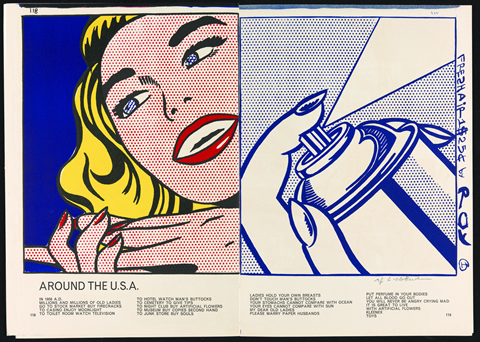

“[The book brought] together the range of current artistic styles that together formed a volume that had the diverse visual character of Ting’s adopted city of New York,” Terry says. The artists whose work was included in the book had yet to achieve the art world recognition that would eventually be theirs; luminaries like Roy Lichtenstein and Andy Warhol were, at the time Ting’s opus was published, Terry says, “largely lithographic neophytes.”

Now, to celebrate the 50th anniversary of Ting’s landmark tome, the de Young has staged a similarly ambitious display of its contents that includes 40-page spreads taken from two copies of the book in the museum’s collection. Of these, 34 feature original lithographs, some alongside letterpress text. Also on display is the screenprinted cover of the book’s standard edition.

“When first conceiving of his singular volume, Ting envisioned a project [as] ‘exciting as Times Square,’ ” explains Terry, who set out to devise a display method that mirrored this dynamism. As such, gallery walls are configured to provide an overview of the book’s four major components—poetry, pop art, the CoBrA artists’ collective (named for artists from Copenhagen, Brussels and Amsterdam) and second-generation abstract expressionism—while a centralized pedestal proffers nearly 20 feet of free-standing page spreads, granting exhibit-goers the opportunity to see the book “unfold.” For Terry, the variety of the artists’ work represented in the exhibit is its most interesting aspect. And, though Ting died in 2010, his story continues at the de Young through Sept. 7.

In the Abstract

In the 1930s, museums, critics and collectors, favoring realist fare from artists like Edward Hopper, largely ignored “abstraction”—until, that is, a group of 29 American abstractionists formed the American Abstract Artists (AAA) to further its cause.

These pioneers and their frequently unheralded efforts to collectively argue for national acceptance of abstraction during the first half of the 20th century is the focus of “Shaping Abstraction.” On view through Jan. 4, 2015, the show also emphasizes the significance of geometry and form via featured abstract works. Of the assemblage shown, 23 pieces demonstrating an array of styles that fall under the abstraction banner were culled directly from the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco’s permanent collections. Show pieces span from the early to mid-1920s to 1965, but most point to abstraction’s most pivotal period, the 1930s. Exhibited artists Burgoyne Diller, Balcomb Greene and Charles Green Shaw were founding members of AAA, but they’re in good company, according to Emma Acker, assistant curator of American art for FAMSF. “The Transcendental Painting Group—a Taos, N.M.-based organization that similarly aimed to defend, validate and promote abstract art—is represented with a canvas by one of its members, Agnes Pelton,” she explains.

Interestingly, and perhaps surprisingly, Acker notes, is the appearance of Rolph Scarlett’s “Untitled,” circa 1950. “[This is] a rare example in his oeuvre of the drip painting technique most famously adopted by the abstract expressionist Jackson Pollock,” she says. Ironically, while Pollock was as a part-time framer at the Museum of Non-Objective Painting in 1939, Scarlett was employed at the museum as a weekend lecturer.

“I like the fact that ‘Untitled’ is the first work that greets you as you enter the exhibition and the last work you see when you leave the show, because it underscores the affinities between works by early American abstractionists, such as Scarlett, and those by abstract expressionists, such as Pollock,” Acker adds.

Coming as a particular surprise to curators was the unearthing of two other striking compositions in the collection: Ilya Bolotowsky’s “Vertical White” (1955), and “No. 4” by Margaret Glapp, a student of the Rudolph Schaeffer School of Design in San Francisco. Although the latter work is not dated, a handwritten notation of “1926,” which marks the year the school was founded, was discovered on the back of the canvas.

Fine Lines

In “Lines on the Horizon: Native American Art from the Weisel Family Collection,” also running through Jan. 4, 2015, the de Young highlights the indigenous arts of the American Southwest through 72 objects, from historic ceramics and textiles to works on paper and wooden sculpture. Together these intricately cultivated materials provide an engaging visual narrative of different groups, places and time periods in western Native American culture.

“[However,] objects should be understood as ‘Native American’ only in the most general way, and instead should be seen as the products of very local and very diverse traditions,” cautions Matthew H. Robb, curator of the de Young’s Art of the Americas collection. Of these cultural groups, the Haida, Kwakwaka’wakw (Kwakiutl), Tsistsistas (Cheyenne), Navajo and Pueblos (Acoma and Hopi, among others) are examined.

“[When] you look at the objects as products of individual makers and artists, that act of making a line—carving it, drawing it, weaving it, painting it—is something that is fundamental to their creation,” Robb says of the exhibit’s “Lines on the Horizon” moniker. “And when you think about the horizon line that characterizes our experience of these places, and the lines of family and cultural descent that kept and keep these traditions alive, that metaphor becomes a powerful link.”

Along with the de Young’s collection of Mesoamerican art with traditions in the ancient Southwest, pieces from the Weisel collection provide new 19th- and 20th-century Southwestern material that, according to Robb, enhances the museum’s existing holdings in Inuit art and indigenous traditions of California basketry. A prolific collector of Native American material and a supporter of scholarly research for both Navajo weavings and Southwestern ceramics, Thomas Weisel has spent 30 years amassing a substantial—and substantially important—collection.

Staging objects of such resounding fragility demands painstaking effort behind the scenes, particularly to protect works of art in an area prone to earthquakes, explains Robb of mount maker Camille Duplantier’s specially created supports for many of the exhibit’s ceramic vessels. He adds, “[The support system is] practically a work of art itself.”

Modern, Mastered

Making its way to the de Young for a summer run (through Oct. 12) is “Modernism From the National Gallery of Art: The Robert and Jane Meyerhoff Collection,” featuring 46 paintings and sculptures organized generationally in three groups from some of the biggest names in postwar American art, including Jasper Johns and Lichtenstein, both friends of the Meyerhoffs. Rounded out with works by Ellsworth Kelly, Roy Rauschenberg, Frank Stella and others, the exhibit is an “unparalleled collection,” promises FAMSF Director Colin B. Bailey in a press announcement.

It’s also a first, as the de Young is the lone venue outside of the greater Washington, D.C., and Baltimore areas chosen to host this exhibition, which is a survey of works stemming from the wake of World War II until the end of the 20th century. Of these prolific offerings, look for stars like Lichtenstein’s “Painting With Statue of Liberty” (1983) and Johns’ “Perilous Night” (1982) to orbit the show’s centerpiece: Barnett Newman’s “The Stations of the Cross: Lema Sabachthani” (1958-1966), widely considered to be the artist’s most important work. “The Stations of the Cross” is presented within a discrete chapel-like space for viewers to experience the 15 paintings as a single work—the way the artist intended. In another room, the museum will screen a film of Newman discussing this incredibly layered work.

The exhibited is co-organized by the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., which received the Meyerhoff collection—the largest donation to the gallery after Andrew Mellon’s gift in 1937. Harry Cooper, the National Gallery’s curator and head of modern art, believes visitors will be impressed by this presentation of the collection.

From postwar American art to an exhibit of abstract-style pieces, the de Young’s offerings this summer are sure to keep visitors inspired and coming back for more all season long.

***

Animate the Night

Friday Nights Series at the de Young Museum is back for a 10th season

Returning to the de Young this summer is the museum’s wildly popular Friday Nights series—the fun after-dark fete that pulls together patrons of all ages and cultural backgrounds. Now in its 10th year, the after-hours program offers live music, dance and theater performances, film screenings, lectures, panel discussions, artist demonstrations, exhibition tours and hands-on art activities. Each week, these offerings and others—programming also calls for curator talks and local artist interactions—center around a new theme, usually associated with an exhibit or piece from the museum’s permanent collection.

Along with specialty cocktails and fresh fare, courtesy of a la carte menus at the de Young Café, there is an opportunity to experience the museum in a whole new light. The festive nighttime backdrop provides a lively stage for events, including dance lessons in the heart of Wilsey Court. Also extending its hours for the ongoing summer soiree is the de Young’s observation tower, which looks over the action and provides a seldom-seen view of Golden Gate Park after dark. Friday night programming continues through November with complimentary entry; admission is required to see galleries and special exhibitions ($10 adults; $7 seniors ages 65 and older; $6 students with ID and youth ages 13 to 17; children 12 and under are admitted for free).